Welcome to another week! Last Friday, I had the pleasure of having an Alexander Technique lesson from Beret Arcaya - she’s a damn good teacher - and the lesson left me with a bit of a pickle to sort through…

Beret’s understanding of the technique is as complete as it gets (and she would say she doesn’t know a thing!). When she teaches coordination, there’s a heavy dose of instruction on the head, neck, and back relationship (among other things like stopping and thinking). But when you write about the technique, you must include everything in more or less equal proportion. This could leave you - the reader - with the impression that everything should be practiced with equal consideration.

To help you prioritise things, remember:

simple, quiet, additive thinking

the head, neck, and back drive coordination

STOP

don’t internally squirm and wriggle about

THINK! Don’t be a space cadet or a multitasking scatter brain!

This is my long winded way of saying that as I write about hand contact today, don’t forget that this contact occurs as a consequence of the balance of the head, neck, and back.

The purpose of this Contact Series is to describe how to assess the quality of the contact that you make with the world around you as you build coordination.

In standing, walking or running you have your feet.

In sitting you have your feet and your bum.

In lying down you have lots of stuff.

And as you pick things up, perform weight bearing tasks like planks, or do complex tasks like type, knit, or play an instrument, you have your HANDS!

What makes hand contact interesting is the diverse nature of the tasks that our arms and hands can do. When our hands make contact with a surface, they are being sent out to perform either a weight bearing activity or a dexterous activity. I really don’t want to go down the rabbit hole of enumerating every type of contact that you cam make with your hands. Instead, I’ll focus my attention on some things to check out while supporting the weight of the body on your hands and knees (like in crawling).

On Hands and Knees

When your hand is resting flat on a surface, you can think of it as functioning like a foot. By this, I mean :

The whole surface of the hand can absorb your weight.

The flexible wrist can roll in or out much like an ankle. This will transfer load to the thumb/pinkie finger and will create various forms of pressure on the wrist, elbow, shoulder, back, and … well you get the idea.

There is a centre between the pinkie and the thumb. When weight is loaded around this point (rather than to the left/right), the arm can support more weight comfortably.

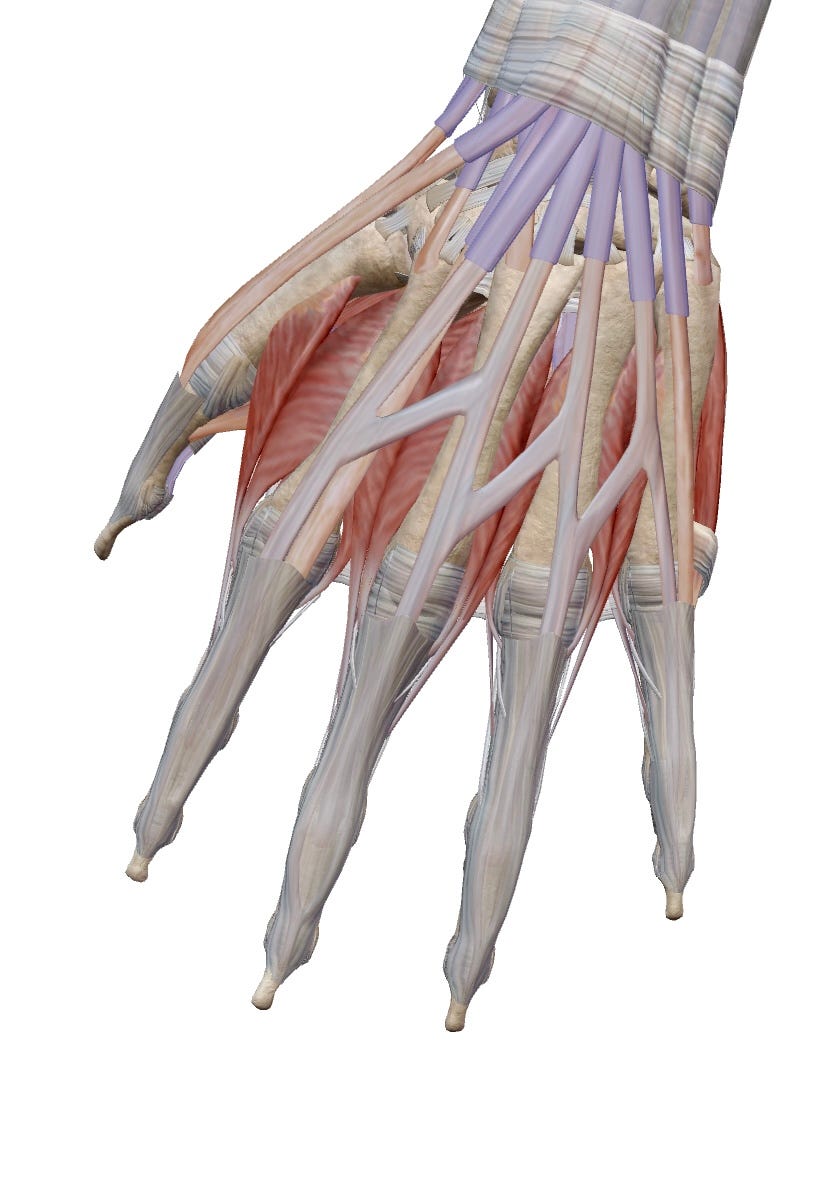

Let’s take a little look at what I mean by this. First, let’s just take a look at what your hand actually looks like. Why? Just cause it’s coooolllll.

All of those ligaments that move the fingers go deep down the forearm. Your flexibility comes all the way from the elbow!

The Arch of the Hand

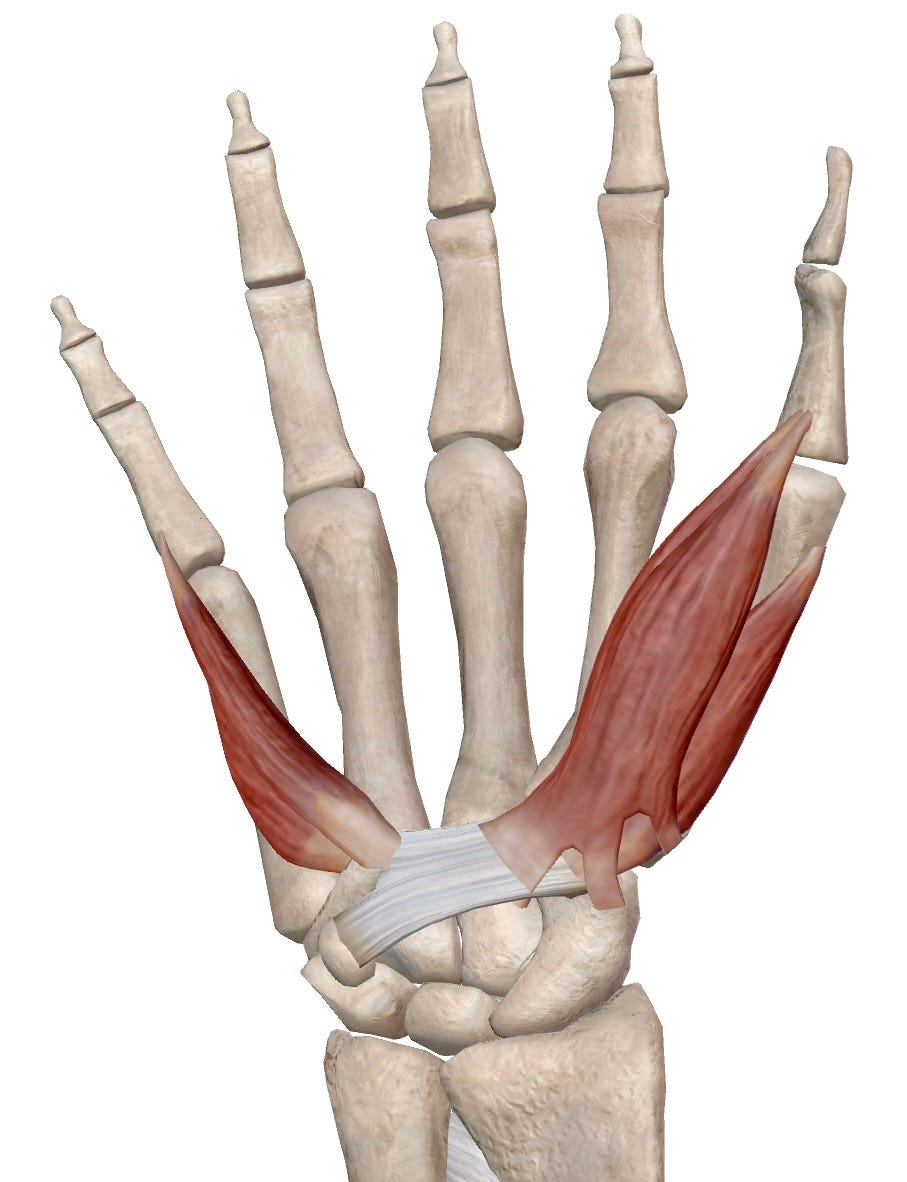

But to show you what I mean by the ‘arch’ of the hand, check out these views!

The picture above shows you the muscle/ligament action needed to bring the thumb to touch the pinkie. What I love about this view is that it clearly shows you this band of ligaments around the base of the hand. Notice that this band is not at the total base of the hand. For my hand, it’s like half an inch above the empty space of the wrist.**

Do Not Splay the Hand Open

When placing your hand on a surface for weight bearing purposes, it would be a very good idea for this band of ligaments to be as wide as possible without forcing the hand into a stretch.

In the first image above, you can see the ligaments of the hand quite clearly. I’m forcing my hand open to maximise the surface area my hand can touch, but as a consequence I’ve lost some of the spongy qualities that the hand needs to absorb weight. The second image shows my hand in a much nicer place for weight bearing.

The Rotation of the Thumb

Based on the amount of tension you have in your arms, you will have differing amounts of contact with the pad of the thumb on the surface. If you have a lot of tension in the hands and arm, you will not be able to experience the full flexibility of the thumb. This includes both the ability to extend the thumb away from the palm and the ability to rotate the thumb.

Wait… I can rotate my thumb? WTF?!?

To show you what I mean by ‘rotate the thumb’, I’ll show you a picture that I took of my hand before doing any Alexander Technique exercises in the morning.

If you compare the image above with the other two, you will notice that you can see different amounts of thumb nail in each. In the image above, the thumb has been rotated away from the camera at nearly 90 degrees! It’s a sign of quite a lot of tension in the arm.

I bring this to your attention because your arm may ‘feel fine’, but you might have a thumb that’s just as outwardly rotated as mine. This is a very important thing to notice if you are performing any refined skill with the hands. In my case, the pad of the right thumb MUST make full contact with the thumb rest of the saxophone in order to free the fingers to move at their maximum speed while bearing the weight of the instrument.

You probably have activities that you perform in your life where this range of motion matters. Fortunately, we don’t need to enumerate all of the activities in the world to figure out what applies to you. FM Alexander worked out a wonderful exercise called Hands on Back of the Chair that address this and much much more. It’s what I do to help with my arm injury and I think it will help you too!

**This arch is frequently referred to as a horseshoe shape by Alexander Technique teachers. When the hand makes contact with a surface, you can think about the thumb and pinkie extending away from the base to build a supple opening of the hand. This thought has nothing to do with contact and everything to do with a Direction